Workshop on Contemporary Rural Issues in India: Day 2

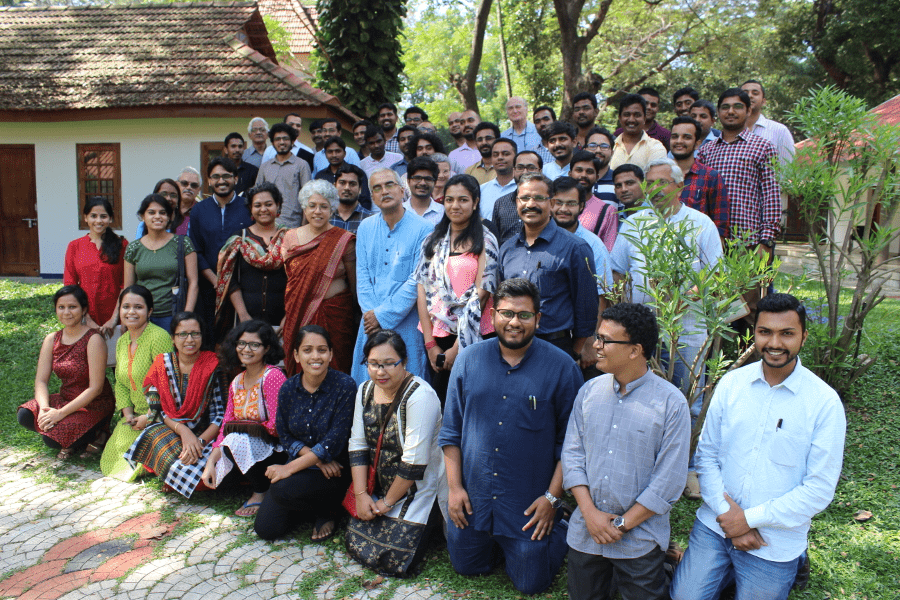

A two-day workshop to explore the research interests of young scholars working in the field of agrarian studies and different socio-economic aspects of rural life in India was organised by the Foundation for Agrarian Studies on December 4-5, 2017, at Cherthala, Kerala. A report on the first day of the workshop is provided here.

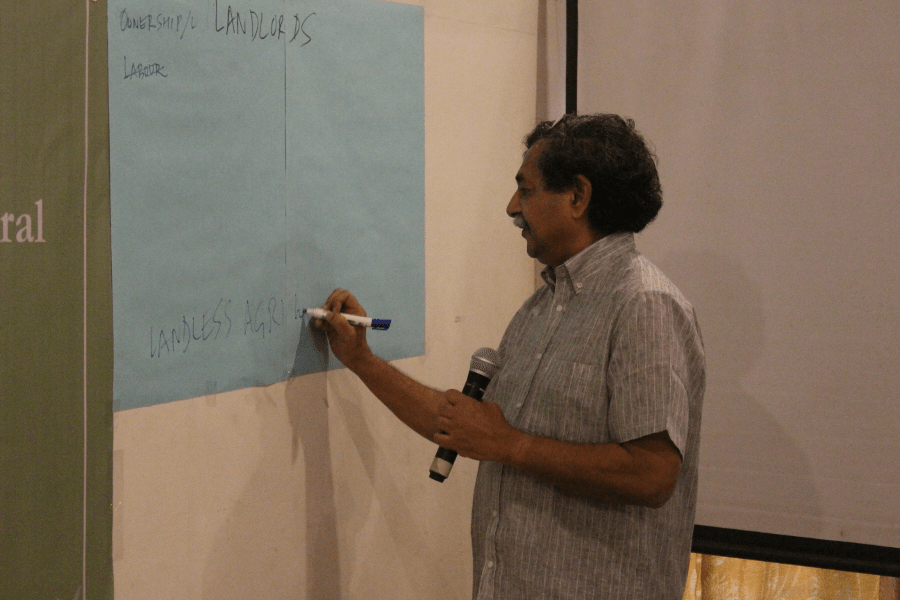

The second day of the workshop began at 8:45 a.m, with a talk by V. K. Ramachandran on identifying classes in the Indian countryside. Professor Ramachandran argued that the agrarian question continues to be the major question in contemporary India. The resolution of this question is essential for the progress of the country. He described the Marxist method of identifying classes and the rigorous empirical studies on which classical studies were based. In India, the pioneering effort in this regard comes from the work of P. Sundarayya. The presentation analysed changes in the socio-economic characteristics in the class of landlords, different classes among the peasantry, and among agricultural and other workers.

In a talk titled “Agrarian Politics, Protest, and Resistance,” John Harriss argued that the nature of the agrarian question in contemporary India has undergone a fundamental change, as has the nature of agrarian struggle. He reviewed the history and changing contours of of agrarian movements in India, and suggested that the most important struggles were those over citizenship and what he termed “the right to have rights.”

The talks were followed by a panel discussion, moderated by Venkatesh Athreya, with Judith Heyer and Shamsher Singh as panellists. Professor Heyer stressed the need to integrate dimensions such as migration and other rural-urban linkages into any enquiry into classes in Indian villages. Commenting on John Harriss’s talk, she highlighted the need to understand political processes at the local level, changing demands in the countryside, and new forms of mobilisation. Dr Singh discussed social hierarchies and sectional deprivation prevalent in rural India. and the importance of these issues in the study of classes in the Indian countryside.

The post-lunch session on the “Impact of Demonetisation and GST on Rural India” began with a presentation by D. Narayana. The talk discussed the detrimental impact of demonetisation on the economic growth of the country. The severity of the impact has been far greater than is reflected in gross domestic product (GDP) numbers. The impact has been particularly devastating for the informal sector. Investment in the private sector has not revived. He of the damage done to the cooperative banking sector by demonetisation policy. Dr Narayana”s analysis also established the failure that demonetisation has been with respect to curbing illegal money.

V. Sridhar’s talk focused on the impact of the newly implemented Goods and Services Tax (GST) on the farm sector. Small and marginal farmers suffered from the double impact of demonetisation and GST. The new tax system undermines the federal structure originally envisaged in the Constitution. In addition, it has created severe problems with regard to access to working capital for small and marginal farmers and those in the informal sector.

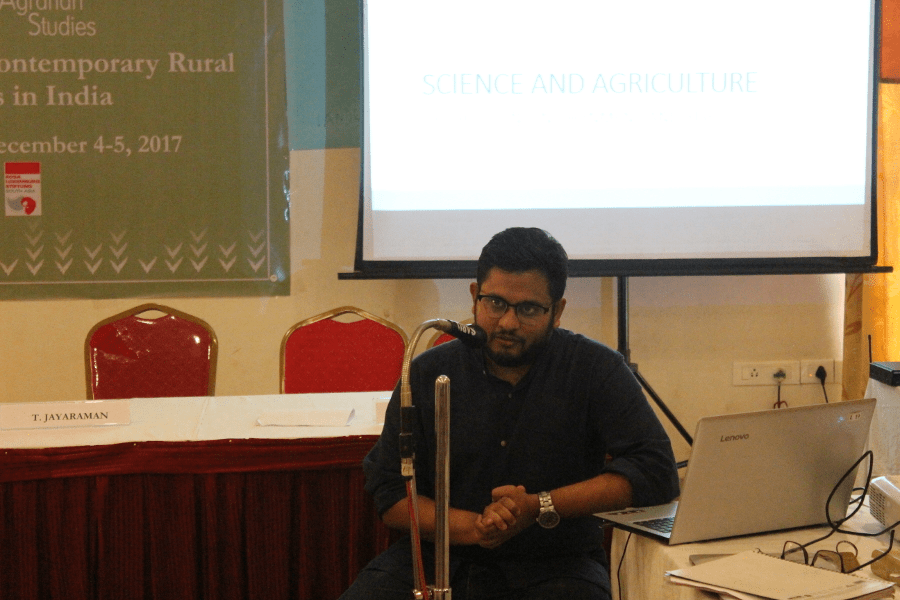

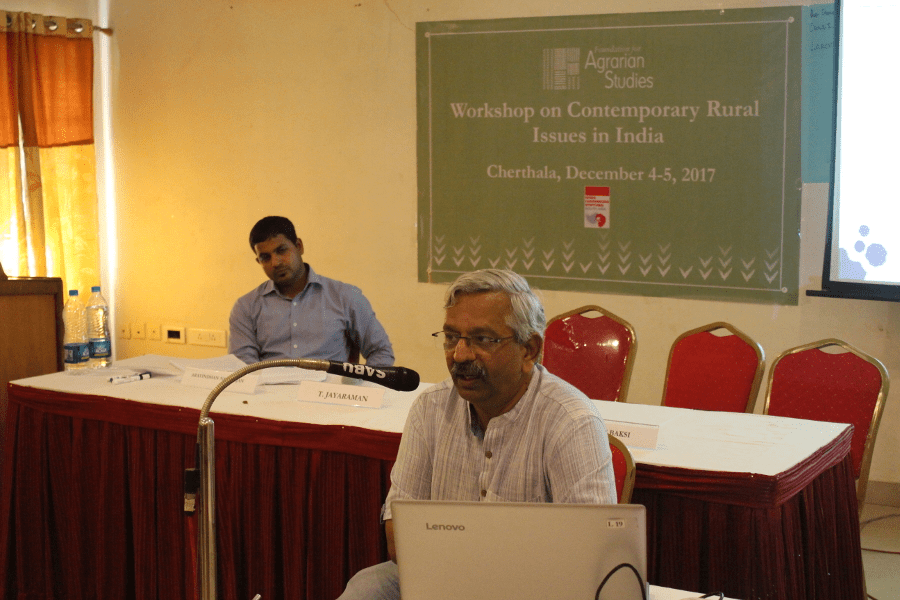

The last session of the workshop was on “Science and Technology in Indian Agriculture.” T. Jayaraman began his presentation by highlighting the persistent concerns regarding agricultural productivity and food security, the well-being of the farming community, and the role that modern science and technology has in dealing with these concerns. Technological growth in an unequal world has a differentiated impact. This also holds true for technological growth in Indian agriculture under capitalism. Big landowners and capitalist farmers benefit from the progressive application of science in agriculture while the cost of the same is borne by everybody, and is particularly harsh for poorer farmers and the labouring classes. In the absence of a proper understanding of economic stratification in the countryside, it might appear that technology is the cause of all suffering. Jayaraman also questioned the tendency to conflate technology with ownership of technology, a point of view that often leads to opposition to technical progress itself. Finally, he responded to the argument that modern science and technology are inherently detrimental to ecological sustainability. Any agricultural policy, he suggested, must take into account issues of productivity, farmers’ and rural workers’ incomes, and environmental sustainability.

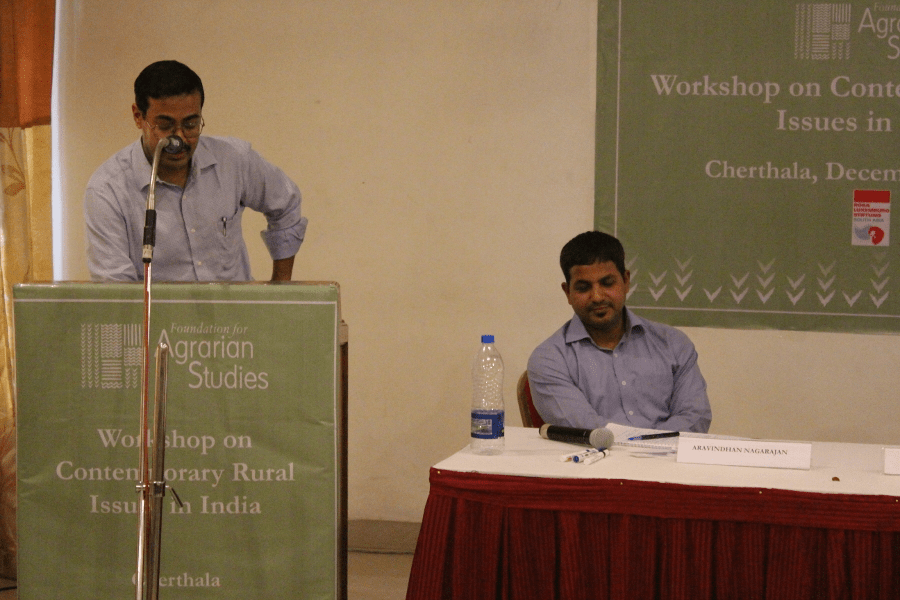

This was followed by a panel discussion chaired by Biplab Sarkar. Aravindhan Nagarajan and Sandipan Baksi were the panellists in the discussion. Aravindhan spoke on the GMO debate in India. Sandipan, drawing on his research on the development of agricultural science under colonialism, spoke of two tendencies in the historiography of science and colonialism. Modern science is often argued to be an appendage of imperialism, with no autonomy of its own. At the same time there is a propensity to argue for “alternative” paths of development that were curbed by the coming of modern science under the aegis of the colonial regime. Referring to the institutional arrangements for agricultural research, experimentation, and education established in the early twentieth century, he argued that while it is a fact that science and technology served as tools for colonial appropriation, they nonetheless provided for better and more efficient ways to utilise nature for human well-being.

At the workshop’s concluding session, Sandipan Baksi thanked the organisers and participants, and expressed the hope that more such workshops — as well as summer/winter schools on a larger scale — would be conducted by the Foundation in future.

A collection of photographs from the second day of the workshop is given below.

Sudha is an Administrative Assistant of the Foundation. She assists the administrative division of the Foundation and also has taken part in fieldwork organised by the Foundation.

Sudha is an Administrative Assistant of the Foundation. She assists the administrative division of the Foundation and also has taken part in fieldwork organised by the Foundation.