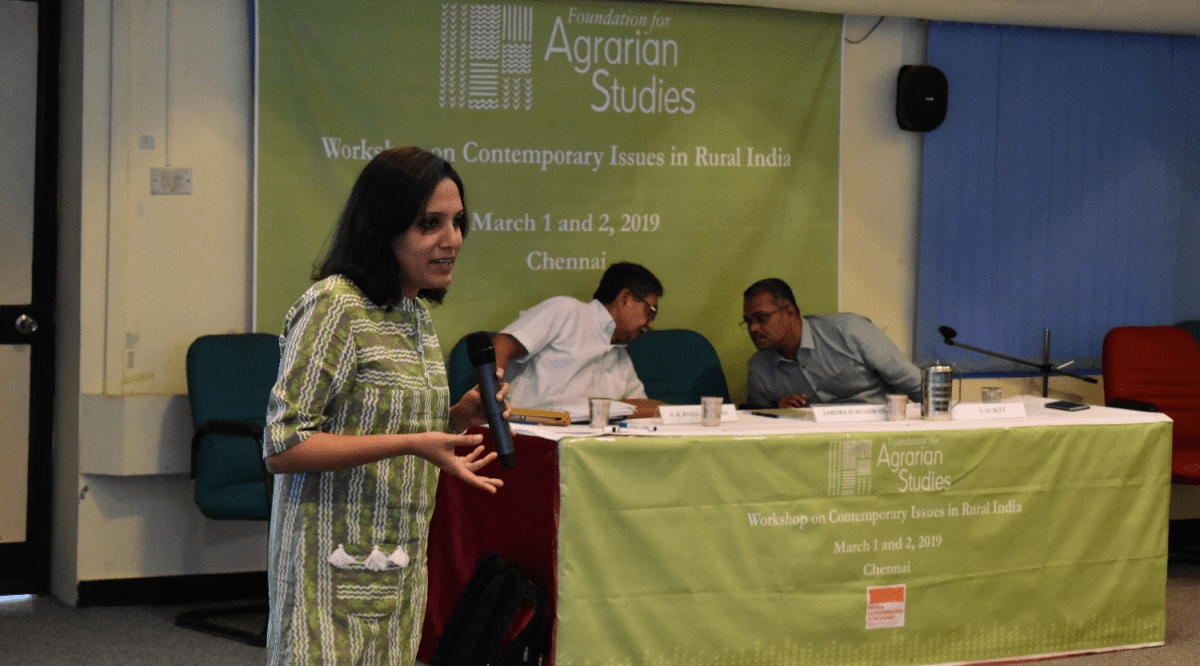

Workshop on Contemporary Issues in Rural India – Day 2

The second day of the FAS Young Scholars’ Workshop on “Contemporary Issues in Rural India” began at 9 am on March 2, 2019, at the auditorium of the M S Swaminathan Research Foundation, Chennai. The first speaker for the day, V. K. Ramachandran, began by emphasising that any progressive transformation of Indian society was not possible unless longstanding issues concerning rural India in general, and the system of agricultural production in particular, were addressed. He deliberated upon the method of village studies, tracing its roots in India to the early twentieth century. He described in detail the limitations of secondary data sources in capturing many significant dimensions of the rural economy, including aspects of land, and employment. Another important variable that is not captured by official sources of data in India is household incomes, which, in turn, asserted Ramachandran, also implied the absence of any realistic estimate of income poverty in the countryside. Village studies as a method of inquiry, he concluded, could go a long way in overcoming these limitations of the secondary data sources.

Aardra Surendran, the second speaker in the session, tried to locate caste in the agrarian structure of rural India. She began by discussing the views of the earliest social anthropologists of rural India, who failed to see the inequality and hierarchy ingrained in the caste structure in Indian rural society, which was followed by a comprehensive critic of such studies. Her presentation looked at the important role played by caste in the realm of agricultural production so as to ensure that a major section of the population worked as agricultural labourers, with no ownership of productive assets, including land. She also discussed the translation of this system of economic domination into all other spheres of village life – the social, cultural, and political. The concluding segment of her presentation deliberated upon the changes in caste as a system of dominance in a changing context, shaped by an expanding market, expansion of democratic politics, rise of caste identities, and so on.

The next session had three speakers S. Niyati, Arindam Das, and R. Ramakumar, speaking on women’s work in rural India, wage rates in rural India, and agricultural credit in India respectively. Niyati described the basic concepts of work as defined by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), Census of India, and the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) in India. She focused on the declining work participation rate among women in rural India, and the increasing casualisation of their work. Arindam Das began his presentation by describing the various official databases that are useful in the study of wages and wage rates. He clearly demonstrated an increase in rural wages between the years 2005-06 to 2012-13, and a subsequent decline.

Ramakumar’s presentation began by laying out the changes in rural banking policies since the period of bank nationalization in 1969. He focused on the changes in the policy framework in the era of financial liberalization. Banks, he asserted, were now distinctly seen as profit making institutions which had to run commercially. The notion of social and development banking has been made irrelevant under the current framework of neo-liberalism. These changes, in turn, have had a severe impact on rural and agricultural banking, resulting in large scale closure of commercial banks in rural India. The share of informal loans has seen a persistent rise in recent decades, and the disadvantaged section of the rural society has systematically been excluded from the reach of formal banking. Unsurprisingly, the dependence on informal moneylending networks has risen. In the concluding segment of his presentation, Ramakumar discussed the revival of formal agricultural credit in the last decade. However, an inquiry into the components of this revival reveals that it has not led to any significant expansion in the reach of formal finance among rural households. Most of the growth in credit figures was due to expansion of indirect finance, much of which was disbursed by urban bank branches. Interestingly, an overwhelming majority of these loans were greater than Rs. ten lakhs each, indicating that small farmers, who constitute more than 80 percent of the farming population in the Indian countryside, are unlikely to have benefited from this revival of rural credit. Ramakumar also showed that most formal loans to agriculture were disbursed in months that did not coincide with the requirements of agricultural production!

The post-lunch session had two lectures. The first was by V. Sridhar who briefly discussed the massive transfer of wealth from the small to the large producer due to demonetization. Brinda Vishwanathan’s presentation on the problem of under-nutrition in rural India began with a discussion on the various indicators of under-nutrition. Her presentation portrayed in detail the anthropometric indicators that show low levels of nutrition in the countryside. She highlighted the failure of the policy framework to translate conditions of high economic growth into reduction in under-nutrition. She also highlighted the urgent need for significant public investment in collection of data pertaining to nutrition indicators.

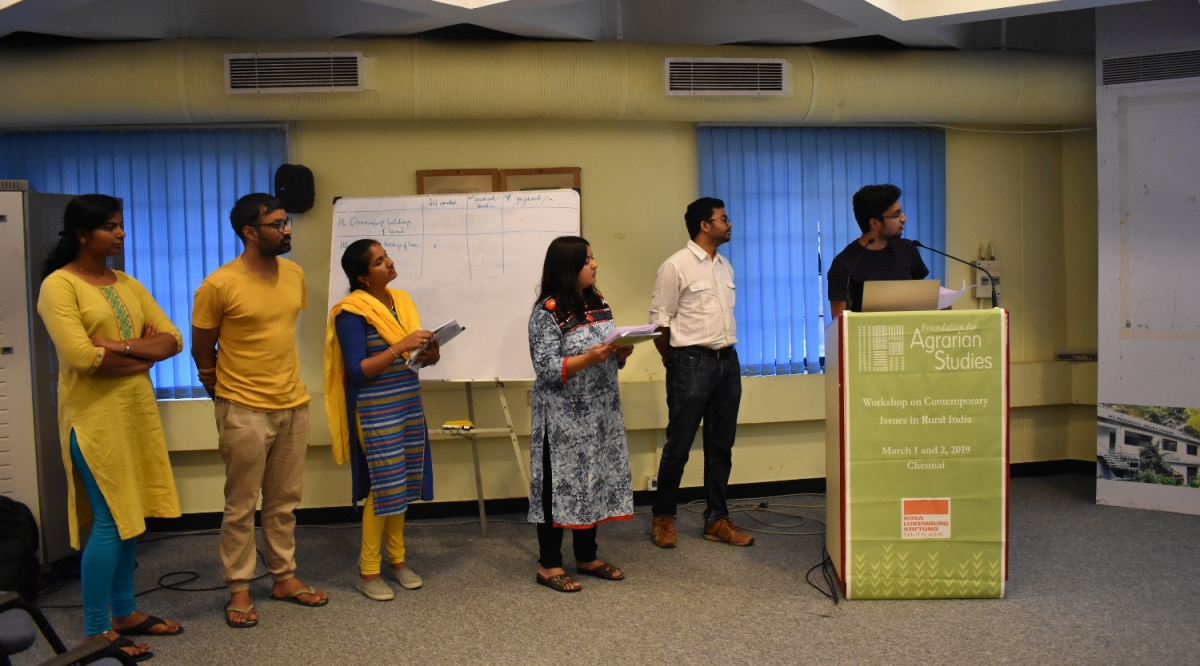

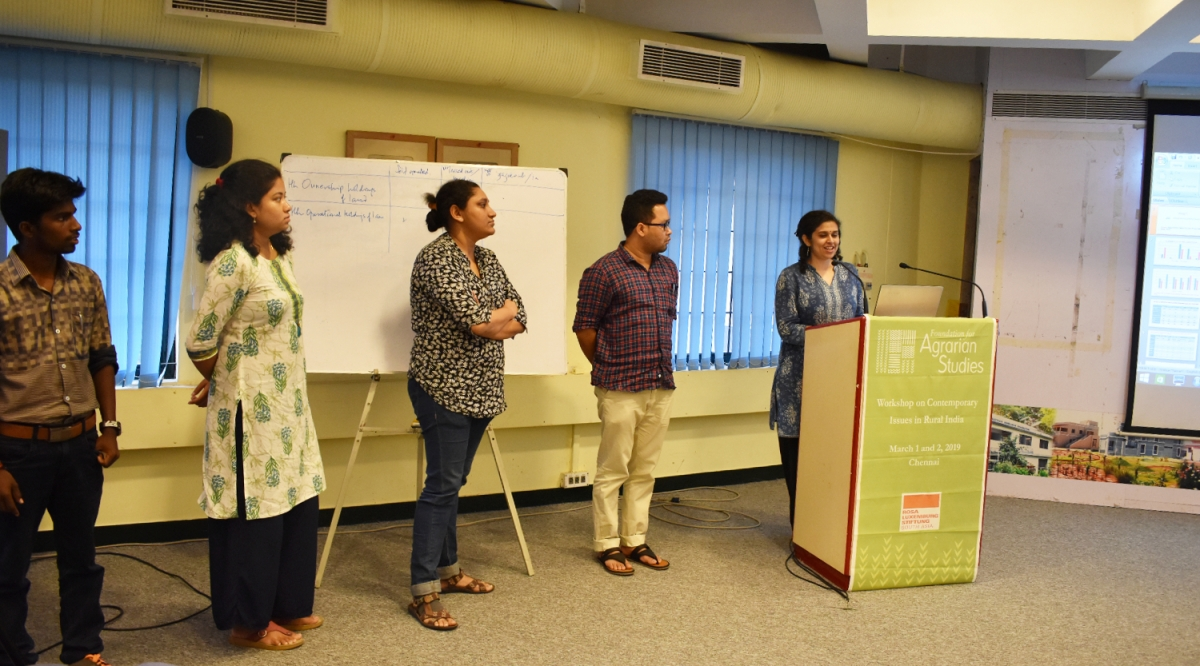

In the concluding session the participant groups presented their respective findings from the exercise from the previous day.

This was followed by a vote of thanks!

Sudha is an Administrative Assistant of the Foundation. She assists the administrative division of the Foundation and also has taken part in fieldwork organised by the Foundation.

Sudha is an Administrative Assistant of the Foundation. She assists the administrative division of the Foundation and also has taken part in fieldwork organised by the Foundation.