The announcement on September 8, 2021 of the Minimum Support Price (MSP) for the upcoming Rabi Marketing Season (RMS) will be seen as adding insult to injury by thousands of protesting farmers who have sustained their agitation against the three anti-farmer Farm Acts for over a year.

This is because the procurement prices offered are not merely grossly inadequate but also because the package comes dressed in what has become a routine deception that the central government tries to pass off on farmers. This is the official claim that the announced MSP adheres to the National Commission on Farmers (NCF) guidelines in respect of remunerative procurement pricing.

The NCF, set up under agricultural scientist M.S. Swaminathan, had recommended a weighted average of C2+50 per cent as the minimum support price at the national level for agricultural commodities, where C2 represents all costs incurred by the farmer during cultivation. The newly announced MSP for Rabi crops for the agricultural year 2021-22, as we show in the following analysis, is only a partial remuneration of the actual cost of production.

The MSP for the Rabi season covers six crops. These are wheat, which is a major rabi crop, barley, gram, lentil, rapeseed/mustard and safflower.

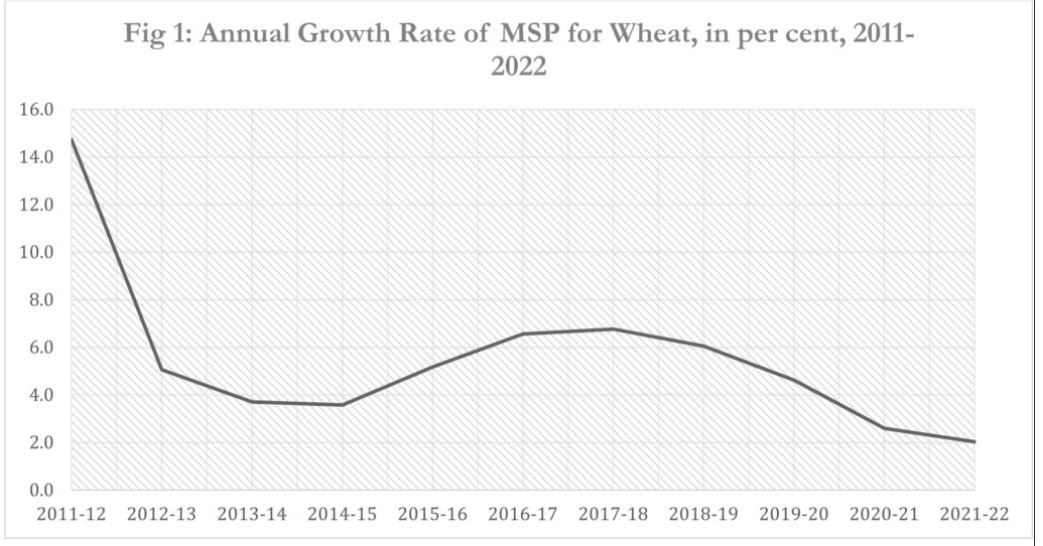

Lowest increase in a decade

If we compare the recent MSP with figures for the past decade, we will see that contrary to the claims of some, this year has seen the lowest increase in MSP for some crops. Take wheat, for example (Fig 1). The year-on-year growth rate of MSP for wheat suggests that in the last 10 years, the highest ever increase was actually during 2011-12, with a 14 per cent increase over the previous year. In the last two years, the MSP for wheat increased by 2.6 and two per cent respectively. Far from being the highest, these were indeed the lowest growth rates of the MSP for wheat in the last decade.

Farmers Commission recommendations ignored

As for the government’s claims of adherence to the formula of fixing the MSP at 1.5 times of the weighted average cost of production, they do not follow the NCF recommendation.

In the NCF formula of C2+50 per cent (for determining procurement prices), C2 refers to the comprehensive cost of cultivation. The main categories of costs under C2 are

1) A2 (value of seed, manures, fertilizers, insecticides and pesticides, irrigation charges, hired human labour, hired and owned bullock labour, owned and hired machine charges, marketing expenses, land revenue and other taxes, interest on working capital, depreciation of implements, and farm buildings, and rent paid for leased-in land);

2) FL (imputed value of family labour);

3) Opportunity costs of cultivation (interest on value of all capital assets and rental value of owned land).

Therefore C2 = A2+FL+Opportunity Costs.

In its calculation of MSP, the government has conveniently left out the significant component of opportunity cost. Thus, not only are the announced procurement prices considerably less than they should have rightly been, the government through this sleight of hand believes it can sell the fiction that it has indeed implemented the NCF recommendations.

Fortunately, we have data from the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) Policy to counter these claims. Let us take the example of wheat. Table 1 shows that during the 2021-22 agricultural year, the projected cost of A2+FL (paid out cost+ imputed value of family labour) for wheat was Rs 1088 per quintal. The announced MSP for wheat at Rs 2015 per quintal does not factor in the opportunity costs. Our analysis however shows that if opportunity costs had been factored into cost of cultivation, the MSP would have been Rs 2277 per quintal, which is Rs 262 per quintal higher than what has been announced. In the case of safflower, the loss for farmers is the highest within the range of the six Rabi crops at Rs 2134 per quintal. For lentil the figure is Rs. 1133 per quintal, for gram Rs 946 per quintal, and for barley Rs. 524 per quintal.

Further, even this meagre increase in MSP has been offset by the sharp increase in the cost of production in this period, and further exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic. Official estimates show that the increase in the cost of production (C2) was 6.5 per cent for wheat in the last year, while the MSP increased by only two per cent. This is so in respect of several other crops, such as barley and safflower. For gram, lentil, and rapeseed/mustard, however, the MSP was higher than the increase in cost of cultivation (Table 2). However, it is well known that procurement operations and MSP are largely concentrated in wheat and are only notional in the case of other crops.

Sharp increase in cost of cultivation: FAS surveys

It is noteworthy that the CACP figures on cost of cultivation, that serves the basis for calculating MSP, are themselves an underestimate. This is because the CACP projected cost of cultivation for any crop season is based on the actual estimates of the crop seasons of previous years with a lag of two to three years (a detailed discussion can be found here). The underestimation in cost of cultivation can be particularly sharp for the period of the Covid-19 pandemic, that has witnessed an absurd rise in input prices.

Cost of cultivation data from recent telephonic surveys conducted by the Pandemic Studies Unit of the Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS) shows that there has been a sharp increase in the cost of cultivation for several crops in 2020-21. This was on account of increases in the cost of material inputs (seed, fertiliser, and pesticides), machine use, and hired labour. The continuous increase in the diesel prices was one of the main reasons for the steep increase in cost of cultivation across states. Farmers incurred higher costs throughout the season for machine use in different agricultural operations like land preparation, irrigation, sowing and transplanting, harvesting, and transportation of harvested produce to the market. Marginal and small peasants, who comprise the majority of cultivators who hire machines for these operations, were affected disproportionately. For instance, the surveys showed that the cost incurred by hiring tillers or tractors for land preparation increased by 10 to 50 per cent in the last one year (kharif seasons 2019-20 to 2020-21). We observed a similar trend for the Rabi season of 2020-21.

In sum, the official data from the CACP reports as well as the findings of telephonic surveys confirm that farmers, especially those with small holdings, have been squeezed by rising costs on the one hand, with inadequate increase in MSP and low procurement levels on the other. The announced MSP shows only minimal growth over the previous MSP and is lower than the C2+50 per cent recommended by the Swaminathan Commission. This onslaught on farm incomes is a serious concern at the time of a pandemic that has accentuated the distress among rural households in India.

Sudha is an Administrative Assistant of the Foundation. She assists the administrative division of the Foundation and also has taken part in fieldwork organised by the Foundation.

Sudha is an Administrative Assistant of the Foundation. She assists the administrative division of the Foundation and also has taken part in fieldwork organised by the Foundation.