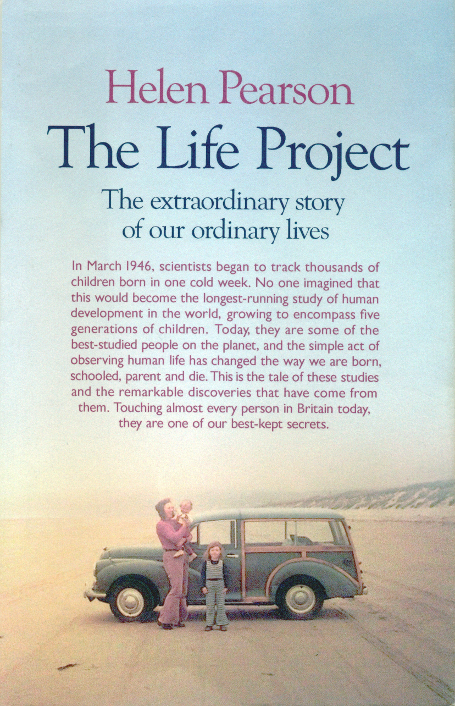

The Life Project, a new book by Helen Pearson, describes the rich history of cohort studies in the United Kingdom.* These are longitudinal studies of individual lives starting from the time of birth and continuing over an extended period. The first cohort study in the United Kingdom was of over 13,000 mothers and babies,all born in one week in March 1946, and the second began 12 years later, in 1958. Three more cohort studies were initiated in 1970, 1991, and 2000.

One of the findings of the 1958 cohort was that of gaps in educational attainment across social classes. At a young age, “56 per cent of children in the top social class were judged to be ‘good readers’ compared with 23 per cent in the lowest social class.” As one newspaper put it at that time, “slow readers may lack an indoor loo.”

Interestingly, while the first cohort and most of the later ones had a clear medical science agenda (epidemiology in particular), the 1958 cohort developed a strong social science component. In 1969, a questionnaire was sent out to the now 11-year olds of the 1958 cohort, and the results written up in a book called From Birth to Seven. Once again, the findings were dramatic (the references here are to occupation-based social classes): “lower class children were not just falling behind at school: they were on average 1.3 inches shorter than their richer counterparts, they had six times as many speech difficulties, and nearly a third had never visited a dentist, in comparison with 1 per cent of the highest class.” The newspapers ran stories with headlines such as “The Unequal Start” and “Must These Children be Lost?”

A paperback titled Born to Fail? summarised the results pertaining to the most disadvantaged children. Disadvantaged children were defined as children “who lived in families with one parent or with five children or more, and inhabited cramped houses or ones without bathrooms and hot water, and had an income of some fifteen pounds or less after rent and bills.”Helen Pearson writes that the scientists responsible for the study that was published as Born to Fail argued that “reducing the inequalities that cripple the life chances of disadvantaged children should be an urgent priority, and that this could be done by a redistribution of income and major improvements in housing.”

We lack such cohort and longitudinal studies in India and are thus unable to empirically monitor the life chances of disadvantaged children and more generally, the extent of economic and social mobility among disadvantaged individuals. It is high time we began such research.

*Helen Pearson,The Life Project: The Extraordinary Story of our Ordinary Lives, Allen Lane, London, February 2016.

About the author

Madhura Swaminathan is Professor and Head, Economic Analysis Unit, Indian Statistical Institute Bangalore Centre. She is also a Trustee of the Foundation for Agrarian Studies.

Sudha is an Administrative Assistant of the Foundation. She assists the administrative division of the Foundation and also has taken part in fieldwork organised by the Foundation.

Sudha is an Administrative Assistant of the Foundation. She assists the administrative division of the Foundation and also has taken part in fieldwork organised by the Foundation.